NICCA Innovation Center

Tetsuo Kobori Architects

11. February 2019

Photo: Takahiro Arai

Tetsuo Kobori Architects answered a few of our questions about the NICCA Innovation Center, a new research center in Fukui, Japan, for NICCA Chemical Group.

Location: Fukui-city, Fukui, Japan

Client: NICCA Chemical Co., Ltd.

Architect: Tetsuo Kobori Architects

Design Principal: Tetsuo Kobori

Project Team: Tetsuo Kobori, Kazuya Iida, Syunya Abe, Osaki Yuta,Rumi Maejima, Yusuke Nakanishi

Contractor: Shimizu Corporation

Engineering: Arup

Landscape Design: Studio Terra

Lighting Design: Izumi Okayasu Lighting Design

Textile Design: Yoko Ando Design

Site Area: 12,360 m2

Floor Area: 7,495m2

The light-filled commons features natural ventilation. (Photo: Takahiro Arai)

Please give us an overview of the project.The chemical manufacturer NICCA Chemical Group commissioned this new research center in the regional Japanese city of Fukui, where it is based. Fukui has been a center of international exchange since ancient times, and the client requested a facility that would be a source of innovation bringing people “from the world to Fukui.” We felt that in order to liberate researchers from the extremely individual activity of experimentation and allow them to share their conflicts and direct emotions with others at the physical level, an open community space for prototyping would be essential.

We glassed in all of the laboratories that had previously been closed off and situated a commons (office) in the center. The commons is a space where people, the natural environment, activities, and tools are constantly in flux. A diverse population uses this space for diverse purposes, leading to cross-fertilization between different ideas and approaches. The “street” running from the first to the fourth floor allows a birdʼs eye view that enables a museum-like multi-layered experience of all of the buildingʼs spaces, while the showroom, cafeteria, and other areas adjoining the street function like an urban bazaar where researchers and other professionals interact. The street thus offers a sequence of encounters that elicit emotions.

Glass walls connect laboratories seamlessly to the commons. (Photo: Takahiro Ahai)

What was most important for you during the design process?During the design phase of the new research center, employees at the client company held seven workshops to reflect on working styles and design. The employees took ownership of the design process, debating the type of building they wanted and how they wanted to work, and we incorporated the results of those discussions into the final design. They continued the workshops during the construction phase as well, discussing the concrete details of working styles, ways of using furniture, and how the facility should function as an open innovation center after construction was complete.

The cubic commons overlap three-dimensionally. (Photo: Takahio Ahai)

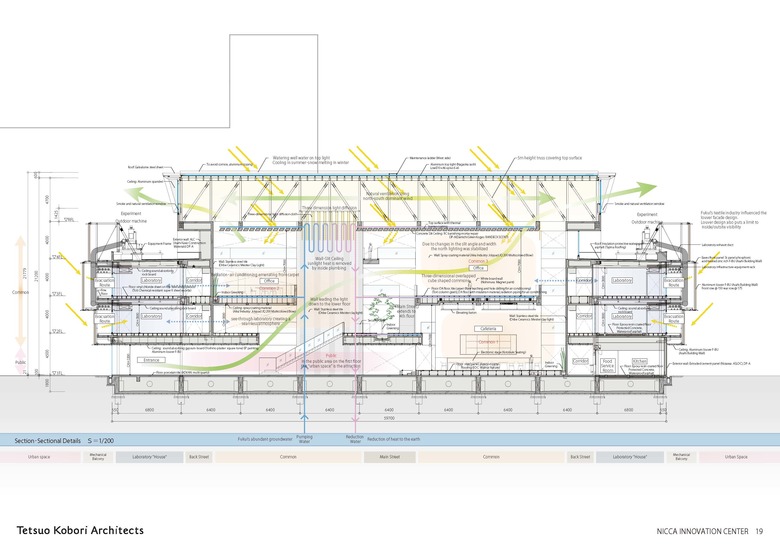

What challenges did you face in the project? How did you respond to them?Fukui has many overcast days, and fewer hours of sunlight than other parts of Japan. Within this context we had two contradictory goals: to make use of Fukui’s precious sunlight and to block excessive heat from solar radiation. Our solution was to cool the sunlight. We ran Thermal Active Building System (TABS) pipes through the floors and walls, removing the warmth from sunlight entering through slits in the concrete slab ceiling so that only the brightness was incorporated into the space. After the groundwater cools the solar radiation, it is used in the laboratories, toilets, sprinklers, skylight-cooling sprinkler system, and for melting snow.

Slits in the ceiling cast bands of light onto the walls for a brief period around the summer solstice. (Photo: Takahiro Ahai)

What did you learn from this project? What will you take from it to future projects?By developing a shared understanding with the client regarding not only the architecture but also topics such as furnishings and approaches to work, we were able to reconstruct the relationship between architecture and people. In particular, transforming concepts into actual spaces through the seven workshops was a new experience for us. Our goal was to create a four-dimensional mesh-like structure in which the natural environment, human relationships, and the information environment intersected in three dimensions and changes over time added the fourth dimension. Case studies of the natural environment and society comprise one aspect of a space, and we believe that to heighten creativity, the structure of that space should be derived from nature.